There was an article is the last issue of Foreign Affairs entitled, “Russia Leaves the West.” In it, the author argues that the attempts by various Western advisors and Russian political leaders in the nineties to bring the Western way of life to Russia and to include Russia in the political institutions of the West were unsuccessful; that Russia, now growing rapidly due to high gas and oil prices, is now self-confident enough to step out on its own and throw off what it perceives as the shackles of Western limitations on the power of state actors.

Indeed, this seems true when you consider some of the high-level goings on of late: the jailing of Yukos CEO, Mikhail Khadorkovsky and the subsequent behind-closed-doors buy out of Yukos by the state oil company Gazprom, the new law that requires all non-governmental organizations to reregister and show how each and every dollar is spent and that prevents any international organization from funding political activities (and almost prevented them from existing).

However, when you walk around small and medium-sized cities, this seems too broad a stroke. Across from the university where I live is a brand new, shiny, western-style mall called МЕГА–СИТИ (Me

ga City transliterated into Russian), complete with a Body Shop, a Sephora, a food court and a fancy new fountain (pictured at right). The floors are so clean you feel a tinge of guilt walking on them. Looking around inside it, you could be in any United States suberb, were it not for the extreme thinness and angular features of the young women (and, of course, the Russian tongues twisting around inside your ears, ringing the occasional familiar note).

ga City transliterated into Russian), complete with a Body Shop, a Sephora, a food court and a fancy new fountain (pictured at right). The floors are so clean you feel a tinge of guilt walking on them. Looking around inside it, you could be in any United States suberb, were it not for the extreme thinness and angular features of the young women (and, of course, the Russian tongues twisting around inside your ears, ringing the occasional familiar note).Most overlooked by this analysis is the obsession of Russian marketers with the English language. No shiny, blinking new sign is complete without at least one English word. Far from the center of the city, in the maze between the main traffic corridors, one can find a restaurant whose name is entirely English and not even transliterated into Russian. (the one pictured below says "Second Hand: Aut Let iz Evropi" I'm not sure what an Aut Let is, but I guess they have them in Europe)

English, it seems, is a signifier of coolness and high quality. Its position as the lingua franca of the West cannot be ignored. While those in power may be seeking to unburden themselves of the promises their predecessors made to Western reformers in exchange for assistance, the relationship of the general population to the idea of the West is not as uncomplicated as “on” or “off,” “in” or “out.”

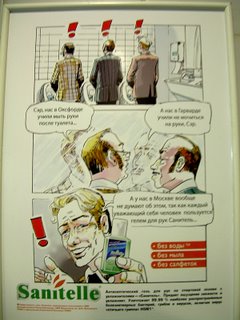

English, it seems, is a signifier of coolness and high quality. Its position as the lingua franca of the West cannot be ignored. While those in power may be seeking to unburden themselves of the promises their predecessors made to Western reformers in exchange for assistance, the relationship of the general population to the idea of the West is not as uncomplicated as “on” or “off,” “in” or “out.” There is an advertisement above a great number of urinals in Moscow. In it, three men are standing at adjacent urinals, apparently finishing up their business. One turns to another and says, “Sir, we at Oxford learned to wash our hands after using the toilet.” The second man says in response, “Ah, but we at Harvard learned not to wash after the toilet.” (A rather strange notion, it seems to me.) Then the Russian man says to the audience, “And we in Moscow don’t think about this, because every self-respecting man uses Sanitelle gel for the hands.” The ad is entirely in Russian, except for the brand name, which is French, I suppose. However, both Anglophones use the transliterated word, “sir,” suggesting that they are actually speaking English. To me, the comparison to Brits and Americans suggests a sort of inferiority complex; as though we are constantly insulting Russians with our superior quality products that we continually export from the West.

There is an advertisement above a great number of urinals in Moscow. In it, three men are standing at adjacent urinals, apparently finishing up their business. One turns to another and says, “Sir, we at Oxford learned to wash our hands after using the toilet.” The second man says in response, “Ah, but we at Harvard learned not to wash after the toilet.” (A rather strange notion, it seems to me.) Then the Russian man says to the audience, “And we in Moscow don’t think about this, because every self-respecting man uses Sanitelle gel for the hands.” The ad is entirely in Russian, except for the brand name, which is French, I suppose. However, both Anglophones use the transliterated word, “sir,” suggesting that they are actually speaking English. To me, the comparison to Brits and Americans suggests a sort of inferiority complex; as though we are constantly insulting Russians with our superior quality products that we continually export from the West.

While there are some substantive differences in quality, it seems to me  that the biggest difference is in marketing (see photo at right, which is an ad for a marketing company called "Marx;" more ironic than a hipster). If there is one thing we are good at in the West, it is selling each other crap. We have spent the last fifty years figuring out clever ways to create demand where there was previously none. I was discussing this with my Russian friends this weekend and I learned an excellent new Russian expression “iz govna sdelat' confeti,” which translates roughly as “to turn shit into confetti”.

that the biggest difference is in marketing (see photo at right, which is an ad for a marketing company called "Marx;" more ironic than a hipster). If there is one thing we are good at in the West, it is selling each other crap. We have spent the last fifty years figuring out clever ways to create demand where there was previously none. I was discussing this with my Russian friends this weekend and I learned an excellent new Russian expression “iz govna sdelat' confeti,” which translates roughly as “to turn shit into confetti”.

To be fair, part of the reason the Soviet Union fell apart was the effect the substantive differences in quality had on Soviet citizens' understanding of their society. And markets, in addition to creating excessive demand for goods and services, also more successfully fulfill the needs of some (not enough) of its participants, by encouraging creativity in ways we easily forget on the American far left. By leaving decisions to decentralized competition for limited resources, we are encouraged to be creative about ways to give others a sense of satisfaction, and hence convince them to give up their money (even if that satisfaction is fleeting and at the expense, sometimes, of the public good).

I believe an essential understanding of this dynamic is still missing from the everyday thinking of Russians, 15 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When the other Fulbrighter and I arrived, we were picked up at the trains station by a young Russian lady who works at the university's office of international affairs. She told me she had briefly been to Berlin and was amazed at how everything was “in order.” “Russia,” she told me, “is too big a country to keep in order.”

The word for order in Russia is poryadok. A common phrase that is used like the English word, “okay” or the phrase “it's all good” is “vsyo poryadkie”, litterally “all is in order.” There is a word, “poryadochny” that is often used to describe Putin and emphasize that he is a good leader. It indicates a link between the concept of order and some intrinsic quality in the person given that adjective. Order, as created by an external authority, it seems is still an important concept to Russians in a way it is not to Westerners. Everyone, for example, Russians and foreigners alike, is required to register with the government, every time he or she enters a new city, and you cannot get a cell phone number without presenting a properly registered passport.. In many buildings (not just state ones), one needs to present identification to get a propusk, a pass which allows one to enter. And (goddamnit) I was not allowed to take photographs in the supermarket in the fancy western mall.

But market economics, which Russia now officially espouses, is all about disorder. Markets work because individuals, and firms that behave like individuals, struggle to make order where there is none. The only successful, sustainable strategy given disorder is to cooperate with others to create stable arrangements that will allow all participants to succeed. Given, there are certain public structures necessary for the kind of cooperation we expect in a modern society, and public institutions are necessary to allow for any kind of justice or fairness to exist in real terms. But the essential orientation required for markets to work is that of individual seeking behavior in the face of disorder. With each market actor looking for some higher authority to place things in order, markets are bound to fail to provide goods and services in sufficient quantity and quality. At the extreme would be market failure. At the moderate degree to which most Russians expect some external source of authority to create order, we simply have a situation where the highest quality goods come from abroad.

As both history and the contemporary state of the world attest, this is an extremely difficult balance to reach. States must be able to step in and create those public goods necessary for cooperation, justice and fairness. But their scope must be limited, so that we each must free to find creative solutions to the world's problems, and thus build order from the ground up, without needing the state's approval. In the West, those in power have simply given up on the idea of fairness, it seems. In Russia, the consolidation of the ruling United Russia party and many of the recent moves by president Putin to limit the mobility of opposition parties indicates an ambivalence toward the limitations of scope of state order. Certainly this is not a return to the Soviet state. No one in the United Russia party is a true Marxist to my knowledge. But, there are still arrangements in place on many levels of society, which require individuals to gain approval from higher authorities, and Putin's emphasis on state approval for political activity seems to reenforce that emphasis.

As much as Russians want to live like Westerners in terms of the quality of products they consume, it seems they are stuck in a sort of triangular struggle. They would like fancy things, but must import them from the West. They would like to take pride in their own ways of doing things, but are constantly comparing homegrown products to superior (and superiorly marketed) Western things. They'd like to improve the quality of homegrown things, but must deviate from their own way of doing things (in which they take pride) in order to do so.

I must say, though, it is nice to be able to buy a fresh loaf of French bread in a shiny new supermarket with English names everywhere. It makes me feel at home almost as well as Russian hospitality.

6 Comments:

Hey Dan,

Nice little blog you've got here. Your last post reminded me a lot of a conversation I had with my Russian friend Yakov. I posed the fateful question, "Do you think there can ever be true democracy in Russia?" To which he asked what exactly I though democracy was, to which I didn't have an exactly good answer. But without extolling Putin's virtues, he explained the idea that he is "paryodochny," like you said, and so was Stalin, and that is why they have both been very successful at what they did. "Paryodochny" is why my Ukrainian host mother changed her vote to Yanukovich, after having voted for Yuschenko twice, because she wanted calm on the streets. I think it's a concept that our American generation can't relate to very much at all. We haven't lived through much bezparyodok in our short lives.

I'll see you in Russia in a couple of weeks probably...

- Susie

That is a good point, Susie. It has been a long since we have had anything as destabilizing as a war or an economic transition on our soil. I would, of course, expect such a thing to make us cling to any order we can get. I suppose this is a problem for neo-cons to solve. If liberal democracy and free market economics depend on a small degree of disorder, how do you manage the need for order that follows the kind of radical transformations that neo-cons espouse. I suppose the wrong answer is 'economic shock therapy.' That's my two sense, anyway.

Oh, and, can't wait to see you in Russia.

Hey Dan,

really nice blog! Keep goin'!

As for the ad above urinals u mentioned....the history was taken from a decade-old well known anecdote just to drive a customer's attention to the necessity of hand sanitizing...

BR!

The second man says in response, “Ah, but we at Harvard learned not to wash after the toilet.” (A rather strange notion, it seems to me.)

You just translated it wrong :)

'Mochitsia' means urinate, not wash. So the 2nd man says: "Ah, but we at Harvard learned not to urinate on our hands" :)

Thank you Alexander for the help with translation. That does help me understand the ad. Do you think my understanding of the usage of English and the comparison to English speakers is still valid? I find I am constantly having to reexamine my assumptions here.

Post a Comment

<< Home